Cultural shock: Phases, symptoms, and how to adapt to a new culture

Moving to a new country usually starts with optimism. You imagine opportunity, safety, and a better future – sometimes all three.

However, once daily life begins, reality can be challenging.

Buying groceries takes longer. Conversations can feel awkward. Simple tasks require careful planning. Even small decisions can become burdensome. That discomfort has a name: it’s called culture shock.

What often surprises people is how normal it is.

Culture shock doesn’t mean you’re ungrateful. It doesn’t mean you made a mistake. And it doesn’t mean the discomfort will last forever. In most cases, it diminishes with time – slowly, sometimes unevenly – but it does fade.

This article will explain what culture shock is, why it happens, its different phases, and practical strategies for how to cope with culture shock effectively.

What is culture shock?

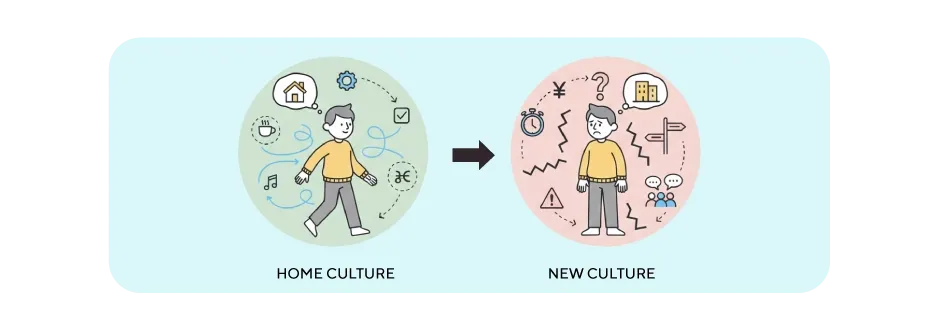

Culture shock happens when your usual way of living stops working.

At home, life runs on autopilot. You know how to greet people. You understand jokes. And you know what behavior is expected. You don’t think about these things because you don’t have to.

Then you move.

Suddenly, the rules change. But no one gives you a handbook.

It’s not just about big differences. Often, it’s the small ones. For instance, how people queue, how loudly they speak, or how directly they say “no.”

Many researchers describe culture shock as a natural adjustment process. In simpler terms, it’s your brain trying to rewire itself. Like switching from one operating system to another. At first, everything feels slow, then frustrating, and eventually, manageable.

Why culture shock happens

Culture shock doesn’t come from a single moment. It builds quietly, over time. Here are a few key reasons why people experience it.

Language barriers

Language is often the first challenge people notice.

Even if you speak the local language, communication can feel draining. Accents sound unfamiliar. Everyday slang carries meanings you’ve never learned. Jokes fall flat, and sarcasm is often missed.  You may understand every word, yet still feel unsure about what the other person truly meant.

You may understand every word, yet still feel unsure about what the other person truly meant.

This constant effort takes a toll. Studies on migration stress consistently show that language difficulty is one of the strongest predictors of anxiety in newcomers.

When expressing yourself feels harder than it should, confidence drops. You may speak less. You may second-guess yourself. Slowly, frustration replaces curiosity.

Different social norms

Every culture runs on unwritten rules. How close people stand when talking. How loudly they speak. When it’s okay to interrupt. How disagreement is shown. These rules feel invisible when you grow up with them. However, when they change, they become impossible to ignore. Without knowing the rules, mistakes are inevitable. You might seem cold when you’re being polite. Or overly friendly when others expect distance. You may walk away from conversations wondering what went wrong.

Without knowing the rules, mistakes are inevitable. You might seem cold when you’re being polite. Or overly friendly when others expect distance. You may walk away from conversations wondering what went wrong.

That emotional uncertainty can be unsettling, and over time, it becomes exhausting.

Daily life feels “off”

Even ordinary routines can feel strange. For example:

- Food tastes unfamiliar

- Time is treated differently

- Humor doesn’t land

- Personal space feels either too close or too distant.

Nothing is wrong exactly – but nothing feels quite right either.

It’s like wearing shoes that almost fit. One step is manageable. A full day becomes uncomfortable. That’s culture shock: constant, low-level friction.

Homesickness and loss of support

Perhaps the hardest part is losing your support system – family, friends, and familiar places. The people who understand you without explanation. Research shows that strong social support can reduce stress substantially. Without it, emotions hit harder. Small problems seem heavier. Bad days stretch on. And even good moments can turn lonely when there’s no one to share them with.

Research shows that strong social support can reduce stress substantially. Without it, emotions hit harder. Small problems seem heavier. Bad days stretch on. And even good moments can turn lonely when there’s no one to share them with.

Signs and symptoms of culture shock

Culture shock doesn’t announce itself clearly.

Most people don’t wake up and think, “Ah, yes, I am experiencing culture shock today.” Instead, it sneaks in through small reactions.

You might notice your patience getting shorter. Or your energy is dropping for no clear reason.

Some common culture shock symptoms may include:

- Feeling frustrated over small things

- Irritability that surprises you

- Loneliness, even when you’re not alone

- Anxiety or a constant sense of confusion

- Strong homesickness

- Avoiding social situations

- Comparing everything negatively to your home country

Some people also notice physical symptoms, such as headaches, trouble sleeping, and changes in appetite. The body often reacts before the mind catches up.

That said, the intensity varies – a lot. Someone who has lived abroad before may feel mild discomfort. At the same time, those moving for the first time may become completely overwhelmed. Neither reaction is negative.

What matters is recognizing what’s happening. Once you name it, it becomes easier to manage.

The phases of culture shock

Culture shock usually happens in stages. Not in a straight line or on a fixed timeline. However, many people recognize these phases when they look back on their experience.

You may move through them smoothly or bounce between them. That’s normal. Without further ado, here are the five stages of culture shock:

Honeymoon phase

This is the early stage. Everything feels new and exciting. The food tastes different. The streets look different. Even small details feel interesting.

If something goes wrong, it feels like a funny story. Getting lost feels like an adventure. Mispronouncing words feels harmless.

For example, you might laugh when you order the wrong dish at a restaurant. Or feel proud just for using a few local phrases.

This phase is full of energy and curiosity. But it doesn’t last forever. And it’s not supposed to.

Frustration (negotiation) phase

This is often the hardest stage. The excitement fades. Daily life begins. And things that once felt charming now feel tiring.

Language mistakes start to feel embarrassing instead of funny. Simple tasks take too much effort. You may feel irritated by rules or habits that don’t make sense to you.

For example, you might struggle to open a bank account. Or feel frustrated when people don’t understand your accent. Even small things, like public transport or customer service, can feel overwhelming.

This phase often includes:

- frustration

- homesickness, and

- self-doubt

Many people think something is wrong at this stage. It isn’t. This phase is actually a sign that your brain is actively trying to adapt.

Adjustment phase

Gradually, things improve.

You start to understand how life works around you. You know which store has what you need. You recognize routines and don’t need directions for everything.

You may still make mistakes, but they don’t shake you as much. You recover faster.

For example, you might handle a conversation in the local language without panicking. Or solve a problem on your own and feel capable again.

Acceptance (adaptation) phase

This stage is steady. You no longer compare everything to home. Differences are accepted without the need to judge them, and daily life runs more smoothly.

You may still miss familiar people or traditions, but that sense of absence no longer takes over. Many people describe this phase as being settled. Not perfect – just balanced.

Reverse culture shock (returning home)

Culture shock can return when you go back home.

You’ve changed. Your habits, values, or perspectives may be different. Things that once seemed normal may now seem strange. For example, conversations may come across as shallow, or you may miss the independence you built abroad.

Culture shock for immigrants in the US

Immigrants in the United States often face a specific kind of culture shock. Not because the culture is “harder,” but because it’s varied.

The US is not one single culture. It’s many cultures layered together.

Social norms

American society often values independence. People are encouraged to speak for themselves, make personal choices, and manage their own lives.

For some, this brings a sense of freedom. For others, it can be isolating. Asking for help may feel uncomfortable at first, even though it’s often expected.

Communication style

Communication in the US tends to be direct, especially in workplaces. While silence can be interpreted as disagreement, speaking up is often seen as confidence, not disrespect.

At the same time, casual friendliness is common. Small talk with strangers happens often, but deep relationships usually take time.

This mix can appear confusing.

Work culture

Workplaces often expect initiative.

Understanding this takes time. Many immigrants worry about doing too much – or too little.

Customer service culture

Customer service is taken seriously. Smiling, politeness, and efficiency are expected in many interactions. Complaints are often encouraged, not avoided.

This could feel strange at first, especially for people from cultures where complaining is discouraged.

Diversity and regional differences

Understanding that there is no single “American behavior” helps reduce frustration. Context matters.

How to adapt to a new culture

Adapting to a new culture doesn’t happen in one big moment. It happens in small, quiet steps. Some days you notice progress, while other days you don’t. Both are normal.

Wondering how to deal with culture shock? Here are some actionable habits that make the process easier:

You don’t need to understand everything at once. Start small: how people greet each other, how punctuality works, and how disagreement is usually handled. These basics reduce stress quickly.

Fluency isn’t required to function. Confidence matters more. Listening helps as much as speaking. Watch local TV or listen to the radio, as it helps build familiarity faster than memorizing rules.

When something seems unusual, pause and ask why it exists. Every culture solves problems differently. What appears inefficient to one person may be considered respectful to another.

Routines bring stability. The same morning walk, the same grocery store, the same weekly schedule – when the world feels unpredictable, routines act like anchors.

You don’t need a large social circle. One or two meaningful connections are far more valuable. Community centers, language groups, religious spaces, and cultural organizations help many immigrants feel grounded.

Adjusting doesn’t mean cutting ties. Hearing familiar voices can calm the nervous system. It reminds you that you haven’t lost your past while building a future.

How long does culture shock last?

Believe it or not, there is no universal timeline for adjusting to a new culture.

For some people, culture shock lasts only a few weeks. For others, it stretches over several months. Some experience it in waves that rise and fall.

The duration depends on many factors, such as:

- Personality

- Language ability

- Past experience living abroad

- Social support

- Stress levels

One important thing to understand is this: adaptation is not linear.

You may seem settled one day, then encounter sudden frustration the next. This doesn’t mean you are starting over – it means your brain is processing something new.

How BOSS Revolution helps immigrants to stay connected

For many immigrants, staying connected to home is not optional – it’s emotional survival.

BOSS Revolution supports immigrants by making it easier to:

- Stay in touch with family abroad

- Send international money transfers

- Provide mobile top-ups for loved ones

These tools do more than solve practical problems. They reduce emotional distance. Knowing you can help family members and hear your ‘loved ones’ voices creates stability during adjustment.

Final thoughts

Culture shock is not a personal failure. It is a natural response to change – especially big change.

Almost everyone who moves to a new culture experiences it in some form: the confusion, the frustration, and the quiet moments of doubt. They are part of the process.

Understanding the phases of culture shock makes the experience less overwhelming. It turns discomfort into something temporary and manageable.

Remember, adaptation takes time. It requires patience and openness – both to the new culture and to yourself. With time, what once seemed foreign starts to become familiar, and slowly, a new place can start to feel like home.

Sources: all third party information obtained from applicable website as of February 10, 2026

-

https://www.ciee.org/go-abroad/college-study-abroad/blog/what-culture-shock-4-examples-and-tips-adjust

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666623524000710

-

https://www.ru.nl/en/radboud-into-languages/news/working-together-in-a-culturally-diverse-team-do-you-know-the-unwritten-rules

-

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10915202/

This article is provided for general information purposes only and is not intended to address every aspect of the matters discussed herein. The information in this article is not intended as specific personal advice. The information in this article does not constitute legal, tax, regulatory or other professional advice from IDT Payment Services, Inc. and its affiliates (collectively, “IDT”), and should not be taken or used as such by any individual. IDT makes no representation, warranty or guaranty, whether express or implied, that the content in this article is current, accurate, or complete. You should obtain professional or other substantive advice before taking, or refraining from, any action on the basis of the information in this article.